Last summer, New Mexico state special agents inspecting a farm found thousands more cannabis plants than state laws allow. Then on subsequent visits, they made another unexpected discovery: dozens of underfed, shell-shocked Chinese workers.

The workers said they had been trafficked to the farm in Torrance County, N.M., were prevented from leaving and never got paid.

“They looked weathered,” says Lynn Sanchez, director of a New Mexico social services nonprofit who was called in after the raid. “They were very scared, very freaked out.”

They are part of a new pipeline of migrants leaving China and making unauthorized border crossings into the United States via Mexico, and many are taking jobs at hundreds of cannabis farms springing up across the U.S.

An NPR investigation into a cluster of farms, which the industry calls cannabis “grow” operations, in New Mexico found businesses that employ and are managed and funded largely by Chinese people. They’re seeking opportunities in a flourishing U.S. cannabis market after the coronavirus pandemic led to a global economic crisis. But some of the businesses have run afoul of the law, even as states such as New Mexico have legalized marijuana.

Getting out of China

One of the workers encountered at the farm in Torrance County is 41-year-old L., who came from China’s central Hubei province a year ago. He asked NPR to use only his first initial because he is anxious about legal prosecution in the U.S. and China.

L. told NPR he struggled to find work in China during the pandemic lockdown. He was forced to move out of his home after a state developer demolished his house to make way for a new project, but his new apartment was never built and he lost his deposit. When L. went to the developer’s office to protest, he got into a physical fight with employees of the company and was jailed.

That was when a disillusioned L. saw videos on Douyin, a sister app of TikTok in China, about people purportedly earning good money in the United States.

“There was one influencer who kept messaging me his pay stubs in California showing how he was making 4-, sometimes $5,000 a month and telling me how easy it was,” L. says. He got in contact with an agent who promised to help him get to the U.S.

Watching Douyin videos, L. learned how to zouxian, or “walk the line,” to the U.S.-Mexico border. First, he flew to Turkey, then Ecuador. He then took a grueling, monthlong trip from South America to Mexico that included buses, boats and a long walk through the hazardous Darién Gap jungle.

“The journey was full of countless trials and tribulations,” says L. He was robbed twice in Latin America and feared he might die from exposure but crossed into the U.S. in May 2023.

On a path also regularly used by Caribbean and South American migrants, now large numbers of Chinese migrants are taking this land route. U.S. border authorities say they encountered 37,000 Chinese people who crossed irregularly into the U.S. southern border last year — more than the past 10 years combined.

Border officials apprehended L. but released him in July, pending review of his asylum claim. He rented a room in Southern California’s Monterey Park, which is home to a large Chinese immigrant community. There, fellow Chinese immigrants introduced him to labor agencies that promised to place workers without documentation for a $100 fee.

One agency’s Chinese-language social media ad for “cutting grass” in a greenhouse caught L.’s eye. It offered to pay $4,000 a month in cash for what seemed like easy work, he says. Borrowing a cellphone, he dialed the number listed.

A supply chain for labor

From California, L. and a handful of other recent Chinese migrants were driven to a New Mexico grow operation called Bliss Farm.

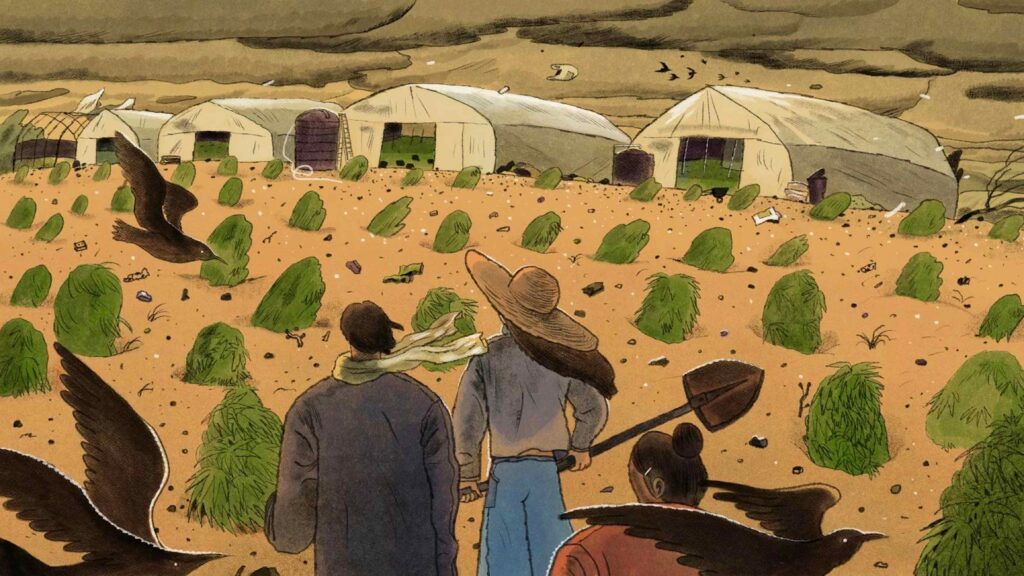

They were shocked by what they saw — a hodgepodge of about 200 greenhouses — but because their phones and passports had been taken by their managers, they felt obligated to stay, workers say.

“The farm said it would cover food and shelter, so you could save all your wages,” a Bliss Farm worker, from China’s northern province of Shenyang, told NPR. “But the farm was just a big dirt field.” He also requested anonymity because he is applying for asylum in the U.S. and fears being sent back to China.

He says he regularly worked 15-hour shifts, alongside the greenhouse’s manager, a man from China’s Shandong province, and the manager’s relatives.

At the end of their shift, the managers left, and the workers slept in wooden sheds with dirt floors, three workers NPR interviewed say. None of them were paid before the operation was shuttered.

New Mexico authorities say a tip about worker conditions and zoning violations led them to visit the farm last year.

“Just a very disastrous grow. There was trash, water, fertilizers, nutrients, pesticides leaking into the ground,” says Todd Stevens, director of the state’s Cannabis Control Division. “As soon as the officer stepped in, I think red flags started going off everywhere.”

Authorities raided Bliss Farm in August 2023.

Sanchez, director of the New Mexico social services nonprofit The Life Link, describes the condition of laborers she encountered there.

“They had burns, visible burns on their hands and arms. … The chemicals, they told me it was from the chemicals,” Sanchez says. “They looked very malnourished.”

L. and two other workers NPR interviewed were among those found at the farm. They’ve applied for asylum in the U.S. and their cases are pending.

“Just a very disastrous grow. There was trash, water, fertilizers, nutrients, pesticides leaking into the ground,” says Todd Stevens, director of the state’s Cannabis Control Division. “As soon as the officer stepped in, I think red flags started going off everywhere.”

Sanchez, director of the New Mexico social services nonprofit The Life Link, describes the condition of laborers she encountered there.

“They had burns, visible burns on their hands and arms. … The chemicals, they told me it was from the chemicals,” Sanchez says. “They looked very malnourished.”

L. and two other workers NPR interviewed were among those found at the farm. They’ve applied for asylum in the U.S. and their cases are pending.

State authorities revoked Bliss Farm’s license and fined it $1 million for exceeding state grow limits.

H/T: www.kuow.org