“You’re one big stinky rat dude,” the email began. “You lack the quality of critical thinking and can synthesize no original thoughts. You’re a follower, a sheep, and a rat.”

I’m assuming that email was about my recent column about stores in Southwest Virginia that are openly selling marijuana over the counter and not one of my political columns because after that cannabis column ran, I got a lot of emails from readers who were unhappy that I had “outed” these stores.

One reader called me a “weed buster.” A few called me words I don’t think I should print. Someone took my Facebook profile picture and circulated it in a cannabis group with this message:

I’m not offended but my cat, Hazel, may have some words to say.

In case you missed it, that column told how I was driving through Marion when I spotted a cannabis store on Main Street. Out of curiosity, I checked it out and wound up buying what I assumed was weed — the clerks didn’t say. In Abingdon, I found another such store, and bought some more. Cardinal’s Susan Cameron later documented how these cannabis retail outlets are proliferating in Southwest Virginia, with at least five within 11 blocks on State Street in Bristol. None of this is legal, of course. State law now allows people to possess small amounts of cannabis (what we old-timers used to call marijuana) but still forbids the sale of whatever you want to call the stuff. Attorney General Jason Miyares has also issued an opinion that membership clubs and “sharing” where money changes hands are also illegal, but that hasn’t stopped these places from operating anyway. I’ll have more to say about the politics of that in a future column, but today I’ll share my latest weed-buying experience.

We had the cannabis I bought in Abingdon and Marion tested and, as that initial column reported, it was very much the real thing. (In case you’re wondering, the samples are all destroyed after testing so, no, I no longer have them.) Unfortunately, I’d only bought enough for a test of cannabinoids, not enough for a test of what else might be mixed in with the product. For that, I was told I needed a bigger sample — at least 3 grams — so I set out to buy more.

Business took me to the New River Valley, so I set my sights on the Good Vibes Shop. The store’s website advertises five locations in Southwest Virginia — Blacksburg, Bluefield, Marion, Radford and Wytheville — and describes itself as offering “a comprehensive range of agricultural services and products.” The website never mentions cannabis. Indeed, the photos show what appears to be lettuce sprouting in a greenhouse; it promises “agriculture and good vibes alike.” I found no lettuce for sale.

The cannabis stores appear to be trying to get around the law by claiming to be “membership clubs” (although Miyares says that doesn’t matter). At the store in Abingdon, I was handed a membership card as soon as I entered. In Marion, I wasn’t, but my first name — first name only, nothing else — was entered into a database. At the Good Vibes stores in Blacksburg and Radford, the two that I visited, a sign was posted outside advising that these were “private” “membership” clubs.

I didn’t go into the one in Blacksburg, I did go into the one in Radford. Two clerks were present, one behind the counter, one out in the customer area. I asked how I could become a member. The clerk behind the counter directed me to a notebook — of the type you might use in a classroom — and told me to write my name and make up a four-digit PIN. I asked if he wanted first and last name, or just first. He said first and last, but I noticed others had only entered a first name. It’s unclear what the PIN was for. If the clerk entered all this into a database, it was done out of my view. If the name and PIN only stay in that notebook, it’s not exactly searchable.

The clerk then asked if I had come to buy CBD, or cannabidiol, a compound found in cannabis. It won’t make you high; another compound, THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol, does that. CBD is a legal product that is often sold as an herbal remedy that some swear by, as well as being the subject of multiple academic studies for its medicinal purposes.

I asked how the CBD purchase worked. The clerk said if I bought some CBD, then they could “share.” He never said what they’d be sharing, but the implication seemed clear. I asked about some of the other products in the store — from decorative items to a mushroom-based product said to have some anti-aging properties — but he said the “sharing” only applied to CBD.

“OK,” I said. “I’ll buy some CBD.”

He asked how much I wanted. I asked how much I could get through sharing; I was mindful of the lab’s advice that it needed at least 3 grams to be able to test for more things than cannabinoids. The clerk said he couldn’t tell me — that doing so would be illegal. Since I’d paid $10 at the other stores for about 1 gram, I guessed and told him I’d buy $30 worth. (Cardinal donors, don’t worry. I’m paying for this out of my own pocket. I don’t think our donors would appreciate me using your donations to buy pot, even in the name of journalism and science.)

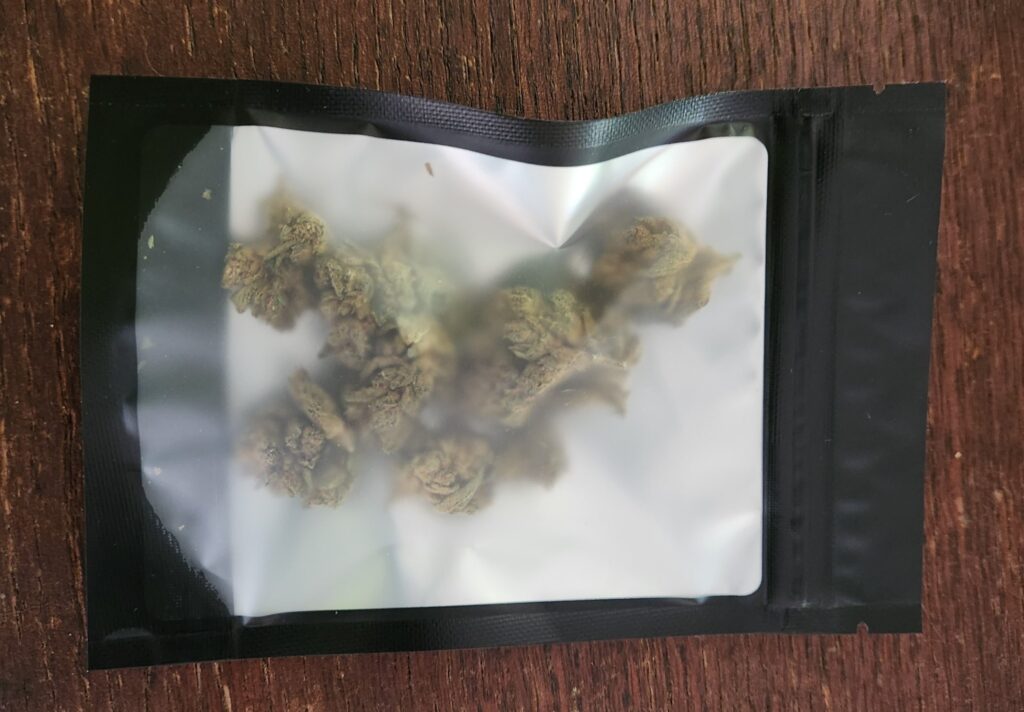

The clerk did ring up $1.49 in tax — making this the only place I’d visited that charged tax — and then handed me a small package that contained something green.

The second clerk then asked if I wanted indica or sativa; the former is a calming “downer” strain, the latter an energizing “upper” variety. I picked indica, although it didn’t matter since I planned to have it all tested. He disappeared into a back room, then returned with a plastic bag with a much larger quantity of something green.

With that, my purchase was complete. It weighed 5.5 grams, so sufficient for the type of lab test we wanted. Those test results have now come back. It tested at 15.86% THC; the legal limit that defines marijuana is 0.3%, so, yes, this is definitely marijuana. The lab also tested for two other things: heavy metals and microbiological impurities, such as mold and various assorted microbes. We then sent those test results off to a variety of people — doctors, cannabis regulators, cannabis business executives — for their interpretation.

The good news: The sample tested was under the state limits for metals and microbiologicals, according to Jeremy Preiss, acting head of the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority, which regulates the state’s medical marijuana programs (and presumably would regulate recreational cannabis if it’s ever legalized). For instance, this sample tested at 0.034 parts per million for arsenic; the state allows 10 parts per million.

The bad news: The science on all this is murky because there hasn’t been a lot of research on cannabis (since it’s been illegal), and there’s a cumulative effect to consuming even “safe” levels of heavy metals.

The University of Virginia Medical School directed me to Dr. Michael Shim, director of pulmonary rehabilitation and director of the Pulmonary Function Testing Lab. As a pulmonary doctor, he’s not a fan of people putting anything into their lungs other than air. He warns that if someone smoked enough of this particular cannabis, “there’s the possibility that it would go over the threshold of what’s recommended.” He suggested I consult the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and its regulations for tobacco.

The FDA sets the maximum amount of arsenic in a tobacco cigarette at 0.1 parts per million; this sample is 0.034, so about one-third of what’s allowed. However, the FDA assumes that anyone smoking cigarettes is willing to assume some risk. By contrast, the Environmental Protection Agency sets the maximum amount of arsenic allowed in drinking water at 0.01 parts per million, so this cannabis sample has 3.4 times as much arsenic as what the EPA would let you drink.

The FDA limit on lead is 0.4 parts per million; this sample is 0.025, so 1/16th the acceptable limit for cigarette smokers. However, the EPA limit for lead in drinking water is flat-out zero.

The FDA limit on cadmium in tobacco cigarettes is 0.1 parts per million; this is 0.063, so a little closer to the threshold but not there yet. However, Shim said, if you smoked enough joints, you’d eventually get there. For what it’s worth, the EPA limit on cadmium in drinking water is 0.005, so this weed sample had 12.6 times as much cadmium as the EPA thinks is safe to consume.

The metal content is consistent with other studies. A study last year by Columbia University found that marijuana users typically have higher levels of lead and cadmium in their bodies than non-users. Cadmium has been linked to kidney disease, among other health problems.

Shim’s same concern applies to the mold content. A lot of black-market weed is grown indoors in damp conditions that are conducive to mold, Shim said. “This is anecdotal, but I do have people who quit smoking, transition to marijuana and they’re persistently coughing with respiratory symptoms.”

The actual scientific data on all that, though, is slim. “We don’t know,” he said. That’s why he believes “if you don’t know, no one should talk about how safe it is.”

Dr. Molly O’Dell, now retired after more than 20 years as a health department director with the Virginia Department of Health (and, disclosure, a member of Cardinal’s community advisory board), said that while the mold might be within acceptable limits, “I’d tell my asthmatic nephew to avoid it.”

We might expect doctors to be cautious about such things. What about others?

“The mold and microbials aren’t at an alarmingly high rate, however, more than what we would sell through our brand (if it was legal flower),” said Tanner Johnson, CEO of Pure Shenandoah, a hemp company in Rockingham County that is among the bidders for a medical marijuana license for the Shenandoah Valley and Piedmont. Some hemp companies insist that the microbe level be zero.

That was a consistent refrain of those who operate in various sectors of the legal cannabis market: This is poor quality cannabis. Trent Woloveck, chief strategy director for Jushi, a Florida-based cannabis company that operates in seven states and holds the state license for medical marijuana dispensaries in Northern Virginia, said he found the heavy metal content “quite high” even if it’s still safe.

“This is something that somebody in California or Oklahoma wouldn’t put into the regulated market,” he said.

Keep in mind that these companies see these rogue pop-up cannabis stores the same way that licensed brewers view moonshiners: as unregulated companies that are taking advantage of lax law enforcement to get into a market that others want to enter legally.

Woloveck also had another observation. He called attention to how there’s no CBD in the sample, while the levels of delta 9 THC are higher than the levels of delta 9 THCA — the latter being the chemical precursor to the former. THCA doesn’t produce a buzz, but, when heated, converts to the buzz-worthy THC. Typically, a plant has a lot more THCA than THC. Because this sample had higher THC levels, Woloveck speculated that this cannabis was grown indoors and then heated. “You can’t grow this out in the field,” he said. “You never see THC higher than the TCHA, so obviously they’re doing something from a remediation standpoint to synthesize the cannabinoid makeup. They’re probably microwaving the weed to get it down to that level of yeast and mold — that’s why there’s a higher level of THC and no CBD.”

He also speculated that the heavy metals might come from pesticides or other chemicals used to encourage growth and discourage yeast and mold. Cannabis is also known as a plant that is a “hyperaccumulator,” meaning it’s very good at absorbing things from the soil it’s grown in, be they good or bad.

Again, these legal cannabis companies have incentive to point out the shortcomings of these unregulated operations, but all this calls attention to a key point: We simply have no idea where this weed came from and, if we hadn’t had it tested, nobody would know what’s in it. Furthermore, because all this is from the black market, we have no idea how consistent any of this is. Maybe this sample comes in under safe thresholds, but there’s no guarantee that the next one will.

That’s the argument for legalizing retail cannabis: The product would be regulated and tested, so consumers know what they’re getting, just as they can be sure when they pick up a bottle of liquor at the ABC store they’re getting bourbon distilled under sanitary conditions and not something cooked up from the radiator of a ’75 Ford Pinto.

Those ABC customers also know the alcohol content of what they’re buying. With black market weed, there’s no way to know what the THC content is until you fire up a spliff — and hope you’re not smoking any contaminants along with it.

All that’s a subject for another day. So is the legality of these operations (I sent a message to Good Vibes to ask how their operations comport with the attorney general’s opinion against sharing but never heard back). Today, let’s return to the circumstances under which I bought this cannabis — or, more technically, had it “shared” after I had paid $30 for a small packet of green material that was purported to be CBD. That sample was way too small to be tested, but it did look like cannabis. As for its street value, based on the current market prices, the value of that small packet was about 3 cents; Woloveck said it appeared to be cannabis “waste product.” That means I wound up paying $30 for 3 cents worth of CBD and in return was “given” 5 grams of marijuana of unknown origin and officially safe but still potentially sketchy levels of metals and microbes.

If you get high enough, maybe you don’t worry about things like that.

H/T: cardinalnews.org