For nearly 17 years, the federal government has been after Charles Lynch for running a medical marijuana dispensary.

Prosecutors refused to drop their criminal case against him even as marijuana became fully legal in California and 23 other states. They refused to let it go when Congress forbade the Department of Justice from using its funds to criminally prosecute medical marijuana activities that were consistent with state law.

Prosecutors have pursued Lynch’s case — which involves conflicting state and federal marijuana laws — through appeals and delays and criticisms that they were spending too many resources on a case that meant so little.

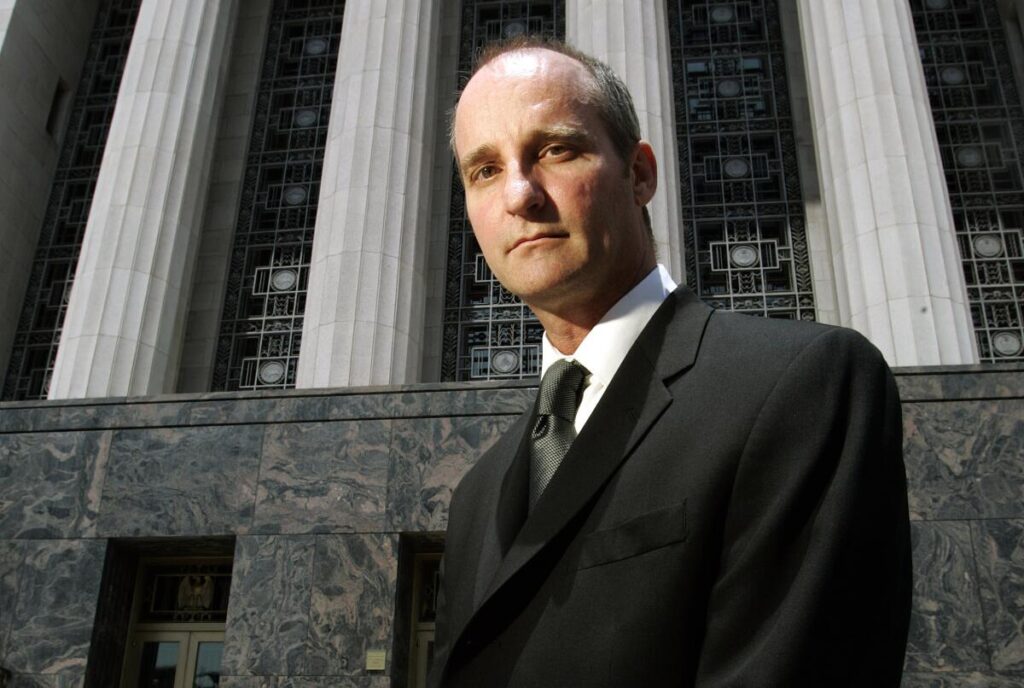

“Twenty-five percent of my life,” Lynch, now 61, said in a Southern drawl at a hearing in downtown Los Angeles this month.

When federal authorities launched their probe in 2007, George W. Bush was in the White House and Lynch was a respected businessman in Morro Bay with a three-bedroom ranch-style house in nearby Arroyo Grande.

These days, he struggles financially, lives in a single-wide trailer on his mom’s property in New Mexico and strains to remember the details of the marijuana operation that got him in so much trouble.

“I’ve lost track,” he testified at the hearing, as his mother looked on.

Lynch and his lawyers have portrayed the case as a pointless exercise by the Department of Justice that has cost taxpayers — who are footing the bill for both the prosecution and his public defenders — millions of dollars.

Even the federal judge has expressed impatience, telling the prosecutor, “at some point in time, this case has to be resolved.”

Why the federal government continued to pursue the case so ardently remains unclear — even this week, when it took a new twist that caught everyone involved by surprise.

::

In April 2006, Lynch opened a medical marijuana dispensary in the seaside city of Morro Bay. As he would later testify in court, dispensaries seemed “like a pretty common business across the state” but there were none in San Luis Obispo County.

Advertisement

Lynch himself used medical marijuana to help with cluster headaches.

“I figured if it could help me along, I understood how it could help other people also,” Lynch said in a recent interview with The Times. “That’s one of the reasons I started up the dispensary.”

The mayor, city attorney and members of the Chamber of Commerce were at the ribbon cutting for the Central Coast Compassionate Caregivers dispensary. A photo captured the mayor shaking Lynch’s hand as he smiled.

Inside the dispensary, Lynch framed his business license and hung it by the front door. Another sign laid out the requirements to purchase marijuana: a valid state ID and a doctor’s recommendation.

Among Lynch’s many customers was Owen Beck, who’d been diagnosed with bone cancer as a teenager and had his right leg amputated. He visited Lynch with his parents to receive marijuana recommended by his oncologist at Stanford University.

Once he began the process, he noted an “immediate change.” He was able to eat and keep food down and his attitude improved.

“I always felt like he was an advocate in my corner,” Beck said about Lynch in a recent interview. . “I didn’t think he was doing anything wrong.”

But while cultivating, using and selling doctor-recommended medical marijuana was allowed under some circumstances in California, federal law — which is independent of those of the states — bans the drug altogether.

“We were still in the Bush administration, and the federal government had not only stuck with blanket prohibition, but they had consistently been expressing concern about state laws and state actors that seemed to undermine or violate these federal law basics,” said Douglas Berman, law professor at Ohio State University and director of its Drug Enforcement and Policy Center. “It seemed like in California … that there was a greater emphasis on enforcement.”

Nearly a year after Lynch opened the CCCC, the Drug Enforcement Administration served a search warrant on the dispensary and his home. Authorities seized around 100 marijuana plants from the sales room.

Months later, in July 2007, authorities arrested Lynch. He was indicted on several counts: Conspiracy to manufacture, possess, and distribute marijuana; providing marijuana to people under the age of 21; marijuana possession with intent to distribute; and maintaining a drug premises.

During a 2008 trial, the prosecutors — including Asst. U.S. Atty. David Kowal — painted Lynch as a common drug dealer who sold pot to teenagers and carried a backpack filled with cash. They said he sold more than $2 million worth of marijuana in nearly a year.

Lynch’s defense attorneys stressed during the trial that he opened his dispensary with “the blessing of his community” and only blocks from City Hall and the police station. They argued that he was told by a DEA official that enforcement on such facilities would fall to local authorities — the implication being that Lynch would avoid federal prosecution if he obeyed the local laws.

That became the basis for their defense, known as entrapment by estoppel, in which a defendant essentially argues that he broke the law based on bad advice from a government official.

Prosecutors argued it wouldn’t have made sense for a DEA agent to tell Lynch that, as there was no way for a dispensary to comply with federal law.

The public defenders faced other challenges in the case, including the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court had prohibited defendants from mounting a “medical necessity” defense. That Lynch believed he was operating under California law was also not a permitted defense.

In August 2008, a jury convicted Lynch on five counts of violating federal drug laws.

“We all felt Mr. Lynch intended well,” Kitty Meese, the jury forewoman, told reporters, including one from The Times. “But under the parameters we were given for the federal law, we didn’t have a choice.”

She added, “It was a tough decision for all of us because the state law and the federal law are at odds.”

The confusion around how to deal with Lynch also seemed to extend to U.S. District Judge George H. Wu. Wu at least twice postponed sentencing Lynch, at one point saying he was inclined to impose a more lenient sentence than the five years required by federal sentencing guidelines.

In June 2009, Wu sentenced Lynch to one year and one day in prison.

Lynch’s lawyers tried to persuade Wu to spare their client prison time altogether.

“As empathetic as I may be to Mr. Lynch’s situation, I have to follow the law,” Wu said. “I feel I cannot get around the one year.”

After sentencing, Lynch told reporters he didn’t think he “should be a convicted felon for doing things that the state of California and the city of Morro Bay told me I could do to help people in our area.”

But he credited Wu for showing “a lot of compassion.”

“The government tried to make me the Pablo Escobar of medical marijuana, and the judge saw past that,” he said.

Lynch’s case was publicized on television and in newspapers nationwide and was eventually made into a documentary called “Lynching Charlie Lynch.”

But the legal battle was far from over.

::

In nearly 17 years, Lynch has never spent a day in prison.

Following sentencing, he appealed his conviction to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. The government cross-appealed, arguing for the five-year mandatory minimum.

As both parties awaited a decision, the landscape around marijuana continued to shift. All the while, Lynch was out on bond and under court supervision.

He watched as Congress in 2014 made a significant amendment to federal law forbidding the Justice Department from using funds in a way that hinders states “from implementing their own state laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession or cultivation of medical marijuana.” It was written into a government spending bill.

Convicted medical pot seller finds congressional allies in legal appeal

May 13, 2015

In a September 2018 decision, the 9th Circuit upheld Lynch’s conviction. In response to the government’s cross-appeal, it found that Lynch was required to be sentenced to the five-year mandatory minimum.

The panel also noted that a dispute existed as to whether Lynch’s activities were legal under state law. The case was sent back to the district court to make that determination — landing it before Wu once more.

In July 2022, one of Lynch’s new federal public defenders, Rebecca M. Abel, filed a motion to stop the government from spending more money on prosecuting the case. She included three expert declarations to show the dispensary was in strict compliance with state law in effect at the time.

Although the government had not backed down, its priorities seemed to shift over the last year. Kowal blew deadlines. Missed a court hearing. Was almost sanctioned.

In a September 2023 declaration to the court, in response to threatened sanctions for not filing a response to Lynch’s motion, Kowal said it “was an extremely slow and difficult project” and noted that he’s “always been a slow writer.”

Kowal declined to comment for this story.

In November, Abel filed a motion to dismiss the case, noting that the government had still not opposed the motion to enjoin spending. She later told the court, “I didn’t know how else to get the federal government to pay attention to Mr. Lynch.”

Four days before a Jan. 22 hearing — in which each side would be able to present evidence on whether Lynch had complied with state law — Kowal asked for more time. In a declaration to the court, he said he misunderstood that the evidentiary hearing would proceed as scheduled amid the motion to dismiss filed by the defense.

”…the government will not be able to effectively go forward with an evidentiary hearing on the dates scheduled, given again, that it needs additional time to prepare the government’s response,” Kowal wrote.

Wu denied the request.

And so, on a recent Monday, the hearing moved forward in the federal courthouse downtown, less than two miles from the LA Wonderland Marijuana Dispensary.

“You’ve changed a lot,” Wu told Lynch.

“I’ve gotten older,” Lynch said, speaking from behind a blue surgical mask.

“We all have,” the judge responded.

That morning, Kowal told the judge he was prepared to go forward with what was already in the court record. He said Lynch’s sworn deposition “will essentially win the case for us.”

Abel slammed her legal adversary, telling Wu that “the government had 18 months to do really anything, and, in the last seven months, it’s done nothing.”

“If I had performed like the government performed, I would have long ago been fired by this court, by my client, been declared ineffective and would have been replaced. I’m not sure why we’re fighting against individuals when this is in fact the United States government,” Abel said. “If Mr. Kowal needed assistance, he had hundreds of people to ask for help. I don’t understand why the scheduling of one individual affects my client’s freedom.”

Around 3 p.m. that afternoon, Abel called Lynch to the stand. He talked about the toll the case had taken on his life, including a bankruptcy in which he’d lost his home.

“I was disenfranchised from working pretty much anywhere,” Lynch said. “No one would hire me considering I have a federal case hanging over my head.”

The hearing lasted hours. The judge took the matter under submission, not yet ruling on whether Lynch had complied with state law.

After the hearing, a Times reporter sent a long list of questions about the case to the U.S. Attorney’s office. What is the motivation to continue pursuing this case 16 years later? Is this case a high priority? If yes, could you explain why Asst. U.S. Atty. David Kowal has missed deadlines, missed a court hearing … and was almost sanctioned?

Before the office responded, yet another filing landed late Tuesday afternoon — the 569th item in the docket.

The government had offered Lynch a plea deal. Lynch said yes.

He agreed to plead guilty to misdemeanor possession of marijuana. Prosecutors would recommend a time-served sentence, meaning Lynch wouldn’t spend a day in prison.

“I’m really just grateful to my family, friends and lawyers for standing by me all these years,” Lynch said in a phone interview Tuesday night. “I kind of felt like it was important for me to take a stand for what I thought was righteous and fair. That’s as true today as it was nearly 17 years ago.”

In a statement, the U.S. Attorney’s Office said the case dated back to a time “when there was a proliferation of illegal marijuana stores across this district that caused significant concern in many communities.”

“Since then, the landscape has changed significantly in California and across the nation,” the statement read. “Upon learning that this case was still active, our current leadership determined that limited prosecutorial resources should not be expended on conduct that today would not be prosecuted by our office.”

Reuven Cohen, one of the original federal public defenders on the case, marveled at how much time had passed. When he first started on the case, he wasn’t married and didn’t have kids. He and his wife recently celebrated their 15th wedding anniversary.

His daughters, now teenagers, “have no ability to understand how this case can still be going on when there’s literally a marijuana dispensary on every single block in Los Angeles.”

Cohen said he originally asked Kowal to allow Lynch to plead guilty to a misdemeanor — telling the prosecutor at the time that, “he was on the wrong side of history.”

“This is exactly what I asked for 17 years ago,” Cohen said.

H/T: www.latimes.com