Cannabis is a broad term that can be used to describe products (such as hemp or marijuana) derived from the Cannabis sativa plant. The terms cannabis and marijuana are often used interchangeably.

The all-encompassing word “cannabis” has been adopted as the standard terminology in scientific publications. Cannabis sativa L is the most widely used recreational drug in the world due to its psychoactive effects on the brain.

According to the 2021 World Drug Report, it is estimated that more than 200 million people consume cannabis, with a high incidence of usage in adolescents.

C sativa L is an erect annual forb that can grow to a height of several metres, with dark green, palmately branched narrow leaves with serrated edges and hairs. Cannabis comprises separate male and female plants. Cannabis preparations are usually obtained from the flowering tops of female plants that are grown together, and they are not exposed to pollen. Lesser concentrations are in the leaves and minimal amounts in stalks and roots.

C sativa contains more than 100 different chemical constituents called phytocannabinoids, which are highly lipophilic and have a low molecular weight (300 daltons). The two most important phytocannabinoids include delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; delta-9-THC), an aromatic terpenoid characterised by tricyclic 21 carbon structure, psychoactive and toxic constituents, and its isomer cannabidiol (CBD), non-psychoactive component, present in low concentrations.

Cannabis exists in various forms. The concentration of THC in cannabis products has increased steadily in recent decades, due to selective plant breeding of cannabis and carefully controlled cultivation conditions of plants. The common preparations are hemp, marijuana, cannabis resin and cannabis oil, which can be smoked, inhaled or ingested. Its potency is based on the THC content of the preparation.

Hemp is defined as any part of C sativa, including the seeds and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers – growing or not – with a THC concentration of not more than 0.3% on a dry weight basis. Marijuana is a herbal form of cannabis prepared from the dried flowering tops and leaves of the plant that has a THC concentration exceeding 0.3% on a dry weight basis.

Marijuana is usually smoked in a hand-rolled cigarette (”joint” or “reefer”), and the THC content can range from 0.5% up to 5%. Cannabis resin (hashish) is the dried and compressed resinous secretions of the plant, produced in the glandular trichomes.

THC concentration vary from 5% to 8%. Cannabis oil (hashish oil) is a concentrated liquid extract of either herbal cannabis material or cannabis resin, soaked in oil (with a higher THC concentration, up to 80%).

What is the toxic dose and mechanism of toxicity of cannabis?

Legalised cannabis for recreational or medical purposes has led to an increase in the number of dogs presenting for THC intoxication.

Cannabis is toxic to pets. An annual list of top 10 pet poisons for dogs of the Pet Poison Helpline included marijuana at number six in 2023.

The intravenous LD50 for THC in rats is estimated to be 28.6mg/kg. Dogs may be more sensitive to the toxicity of THC than humans due to a larger number of cannabinoid receptors in the brain (cerebellum, brainstem and medulla oblongata).

In dogs, the lowest dose at which clinical signs of poisoning appear following ingestion is 84.7mg/kg. Young dogs appear to be more susceptible than adults (median age of one year).

A retrospective review of 80 children younger than six years old who ingested commercial edible cannabis reported that 1.7mg/kg correlates with severe toxicity. Hartung et al (2014) reported that the LD50 for THC in humans is estimated to be around 30mg/kg.

According to the US Animal Poison Control Center, cannabis intoxication mostly commonly affects dogs (96%) and more rarely cats (3%). Approximately 66% of the marijuana exposures reported to Pet Poison Helpline involved pets ingesting homemade or commercial cannabis edibles (CEs) by mixed cannabis extracts with food.

CEs are available in many forms, including baked goods (such as brownies, cookies, muffins or toaster pastries); gummies and candies (such as lollipops, caramels or hard candies), marijuana-infused drinks (for example, juices); lozenges; and butter or oil used in the baked goods (“cannabutter” or so called “hash cookies”, acquired by placing parts of the plant in butter or oil). These items are enticing to young children and pets. Many of the CEs can contain higher concentrations of THC, which varies from product to product (10mg to 30mg).

The second-most common source of cannabis exposures (19%) involved ingestion of plant material (such as dried cannabis, joint butts of marijuana or cannabis concentrate). The average marijuana cigarette contains 60mg to 150mg of THC.

Accidental inhalation of second-hand cannabis smoke can also be harmful to dogs (so, do not exhale marijuana smoke in a pet’s face).

Another source of poisoning is human faeces in parks or on trails. In humans, approximately 65% to 90% of an oral dose is excreted in the faeces as active metabolites (8-OH-THC).

The toxic effects of THC are due to activation of specific cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2.

The CB1 receptors are found in the CNS, predominantly located in the brain. The highest densities are found in the cortex (emotional and behavioural control), hippocampus (cognition), basal amygdala and cerebellum (motor coordination), with a predominantly presynaptic localisation in axons and nerves.

The presynaptic localisation of CB1 receptors suggests a role for cannabinoids in modulating the release of neurotransmitters from axon terminals.

Other locations for CB1 receptors include the peripheral nervous system, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal tissues.

The CB2 receptors are abundantly in cells of the immune system (macrophages, spleen, tonsils and thymus), peripheral nerve terminals and vas deferens.

The CB2 receptors are involved in reducing inflammation. This distribution is consistent with the clinical effects elicited by cannabinoids. The cannabinoid receptors are of the family of G protein-coupled cell-membrane receptors.

The CB1 cannabinoid receptors inhibit an intracellular enzyme adenylyl cyclase (AC), which catalyses the conversion of adenosine triphosphate to cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP; or second messenger), resulting in decreased cellular cAMP levels, and lowering protein kinase A.

This causes inhibition of calcium influx of Ca++ through voltage-gated calcium channels (playing a role in synaptic transmission at CNS synapses), and stimulation of potassium channels (playing a role in neurotransmitter release).

The CB1 receptors, by inhibiting AC, work to suppress the retrograde release of excitatory neurotransmitters (such as acetylcholine, glutamate, norepinephrine and dopamine) or inhibitory neurotransmitters (such as gamma-aminobutyric acid or serotonin).

This can result in either stimulatory or inhibitory clinical signs.

This neurotransmitter modulation may contribute to the central and peripheral effects observed in cannabinoid toxicity. The CB2 receptors mediate inhibition of AC.

THC exerts toxic effects through several mechanisms.

CNS toxicity

THC, being highly lipophilic, easily crosses the blood-brain barrier and exerts its CNS toxic effects by binding at specific CB1 receptors in the brain – particularly at cerebellum (movement control) and hippocampus.

Hypothermia

Administration of THC 30mg/kg intraperitoneally to male Sprague Dawley rats significantly reduced body temperature for up to 6 hours.

Gastrointestinal toxicity

Stimulation of higher centres of the limbic cortex and hypothalamus by THC lead to nausea and vomiting.

Cardiovascular toxicity

Activation of the CB1 and CB2 receptors found in the cardiovascular system lead to acute bradycardia, hypotension and peripheral vasodilatation. Thrombus formation in small cardiac vessel can occur with a risk of myocardial infarction.

What are the clinical features of cannabis poisoning in dogs?

The onset of clinical signs is rapid via either inhalation of smoke (within minutes) or ingestion (30 to 90 minutes), and can last up to 72 hours (long serum half-life of THC in dogs is 30 hours).

Clinical features of poisoning include the following signs.

CNS signs

- lethargy

- disorientation

- hyperesthesia

- static ataxia (pronounced in the hindlimbs)

- tremors

- severe hypothermia (less than 32°C)

Gastrointestinal signs

- vomiting (hyperemesis)

- abdominal pain

Cardiac signs

- bradycardia

- severe hypotension (normal blood pressure range 131mmHg to 150mmHg [systolic] and 74mmHg to 91mmHg [diastolic])

Renal signs

- Urinary incontinence/urine dribbling (CB2 receptors in the vas deferens)

Ocular signs

- glassy-eyes

- mydriasis

Death is a result of sudden cardiac arrest.

In humans, ECG changes are observed with transient marked sinus tachycardia with negative T waves in the inferior leads.

Over-the-counter (OTC) human urine drug screening tests may be unreliable for the detection of cannabis toxicosis in dogs. Unlike humans, dogs with cannabis exposure do not seem to produce large quantities of an inactive metabolite 11-COOH-THC, or THC-COOH in urine. Most OTC human urine drug screens can qualitatively detect THC-COOH when the concentration is higher than 50ng/mL, which is not reached in samples from dogs exposed to cannabis.

What is the approach to managing cannabis poisoning in dogs?

No specific antidote exists for cannabis poisoning. Treatment is recommended for any amount of cannabis ingested.

Life-threatening toxicosis is possible. Treatment is largely symptomatic and supportive.

Supportive therapy

Controlling seizures

Convulsions should be controlled and may require attention for more than 24 hours. An IV catheter should be placed.

To control seizures, diazepam (0.5mg/kg to 2mg/kg IV bolus) should be administered and repeated if necessary within 20 minutes (serum half-life in dogs is 2.5 to 3.2 hours) up to three times in a 24-hour period, or 1mg/kg to 2mg/kg rectally.

Do not give diazepam intramuscularly. This is contraindicated in patients with severe liver disease, however.

Alternatively, administer lorazepam (long-acting benzodiazepine 0.2mg/kg IV bolus), because of its high affinity for benzodiazepine receptors in the CNS, or midazolam 0.2mg/kg to 0.4mg/kg IV may be repeated once.

When IV access is not available, midazolam can be administered intramuscularly because it is rapidly absorbed by this route.

Ketamine used alone causes muscle rigidity and could potentially exacerbate seizures and tachyarrhythmia. Valproic acid is also not recommended (serum half-life in dogs is between 1.5 and 2 hours).

If seizures persist or recur, administer propofol (3mg/kg to 6mg/kg IV initial bolus) followed by 0.1kg/min to 0.6mg/kg/min CRI. Alternatively, 2% to 2.5% concentrations of isoflurane alone with oxygen can also be used.

For maintenance, use 1.5% to 1.8% concentrations of isoflurane in oxygen. Attention to the airway and breathing is paramount.

Affected animals should be intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube to keep the airway clear and provided oxygenation during convulsions. ECG and continuous cardiac monitoring should be performed.

Treating vomiting

Severe vomiting should be treated by antiemetic serotonin antagonists with powerful activity, such as ondansetron (0.5mg/kg to 1mg/kg IV slow bolus [2 to 3 minutes] every 8 to 12 hours, used cautiously in dogs with the MDR1 mutation) or dolasetron (0.6mg/kg IV slow bolus every 24 hours).

Do not use maropitant (neurokinin-1 antagonist) if the patient is at risk for a foreign body obstruction. Metoclopramide (dopamine antagonist) is contraindicated, as excitatory effects can occur.

Intravenous fluid therapy

Hyperemesis can lead to severe dehydration. Intravenous infusion is the preferred means of delivering fluids to severely dehydrated animals.

Fluid therapy with intravenous sterile sodium chloride 0.9% should always be the first-line management.

The volume (mL) of fluid needed to correct dehydration is calculated from the following formula:

Percentage of dehydration × bodyweight (kg) × 1,000

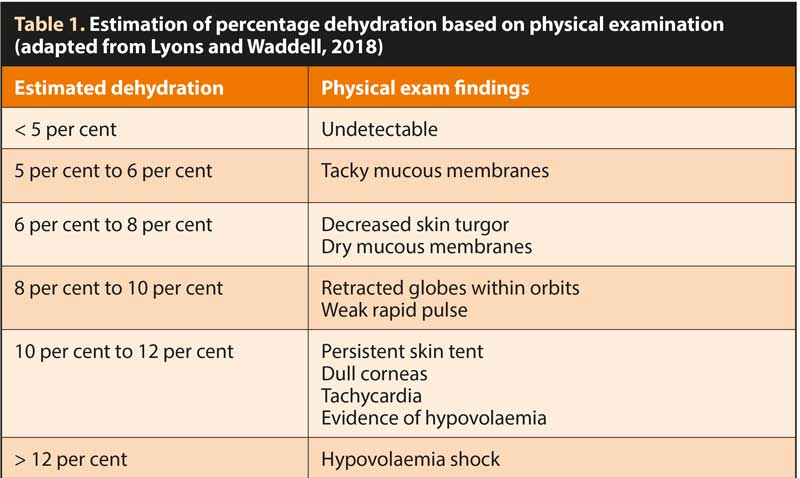

Percentage dehydration can be estimated by examining mucous membrane moisture, skin turgor, eye position and corneal moisture, as described in Table 1.

It is recommended that one-quarter to one-half of the estimated dehydration deficit be replaced over the first two to four hours, with the remaining dehydration deficit and maintenance isotonic volumes administered over the subsequent 20-hour to 22-hour period. Adequate hydration and urine output (1mL/kg/hour to 2mL/kg/hour) should be ensured.

Treating bradycardia

Atropine sulfate is the first-line medication for the treatment of bradycardia (heart rate lower than 160bpm in puppies, 100bpm in small adult dogs and 60bpm in large adult dogs).

Administer 0.04mg/kg IV bolus. This can be repeated every five minutes for a maximum of three doses.

Treating severe hypotension

Administer dopamine (catecholamine, positive inotropic agents, which improve blood pressure): 1 µg/kg/min to 3µg/kg/min CRI.

Treating hypothermia

Severe hypothermia is a medical emergency that requires active core rewarming, such as warm intravenous fluids, to 40°C to 41°C. Fluids can be warmed using numerous methods (such as the immersion of intravenous tubing in warm water, microwaving the fluid bag or in-line fluid warmers).

The patient should be actively monitored until the normal body temperature (38.6°C) is stable for two hours.

Detoxification therapy

Emesis can be performed within 30 to 60 minutes after ingestion, if the patient is asymptomatic, and spontaneous vomiting has not occurred.

Administer apomorphine 0.03mg/kg IV (preferred) or 0.04mg/kg IM. If injectable formulations are not available, use of tablets placed in the conjunctival sac can be considered. Use a 0.025mg tablet crushed and dissolved in physiological saline. Instil in the conjunctival sac and rinse with water or saline solution (0.9% solution) after emesis has occurred.

After emesis, flushing of the conjunctival sac to avoid protracted vomiting may be recommended. Alternatively, use xylazine (1.1mg/kg SC or IM).

Massive ingestions of any form of plant material may benefit from gastric lavage with the patient under anaesthesia and its airway secured (an inflated endotracheal tube will prevent liquid from entering the airway).

To prevent further absorption of THC from the intestinal tract, use activated charcoal (1g/kg to 4g/kg) mixed with water to make a 20% slurry (1g/5mL water) via a nasogastric tube as soon as possible post-ingestion, and after the airway is secured.

Repeated administration of activated charcoal is beneficial because THC undergoes enterohepatic recirculation, so repeating the administration of activated charcoal every 8 hours for the first 24 hours may be beneficial (activated charcoal can interrupt enterohepatic THC recycling). Activated charcoal admitted orally is contraindicated in convulsing or comatose animals.

Because THC is highly lipid soluble (log P values of 7.29), consider lipid emulsion therapy: an initial intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE) 20% 1.5mL/kg IV bolus over one minute, followed by a CRI of 0.25mL/kg/min for the next 30 to 60 minutes.

In non-responsive patients, an additional intermittent bolus can be given slowly, up to 7mL/kg IV. If clinical signs do not improve after 24 hours, discontinue ILE. ILE 20% preparations are isotonic and can be given by a peripheral vein or in a central catheter using aseptic techniques.

Patients should be kept warm and quiet, with minimised sensory stimuli. If recumbent, the body position should be rotated every four hours to prevent decubital ulceration and ocular lubrication every four to six hours. An incontinent patient may benefit from a temporary urinary catheter.

Moderately symptomatic cases may require 24 to 36 hours of care, whereas severely affected cases may require up to 96 hours.

Keep all forms of cannabis out of the reach of pets. Since pets have a good sense of smell, they may be tempted to eat candies, chips, baked items and cannabis flowers (buds).

Consider storage in sealed containers (to reduce smell) and in locked upper cabinets (closer to the ceiling) when not in use. If smoking, keep pets in a separate and well-ventilated room (or outside), away from the smoke.

Use of some of the drugs referenced in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

H/T: www.vettimes.co.uk

You can view the whole article at this link Canine cannabis toxicosis: diagnosis and treatment