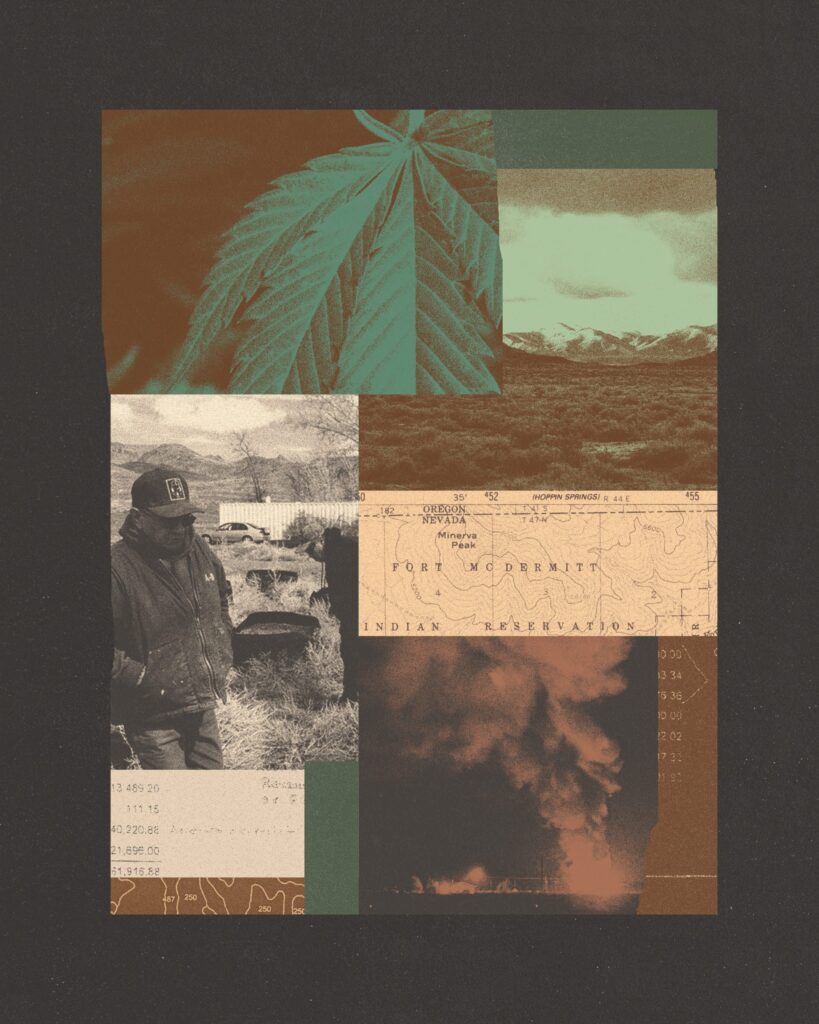

It was a September night in 2020 when the fire torched the Red Mountain Travel Plaza. Residents of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Nation watched as the only gas station and grocery store for miles around vanished amid towering orange flames and acrid smoke.

The convenience store was where the community’s approximately 250 residents went to buy snacks, tobacco and essentials. Without it, they would have to drive more than an hour for major provisions. What’s more, a safe stashed in the back room of the store, which tribal officials said held nearly $19,000 in cash, allegedly burned up. These represented a portion of the profits from a cannabis farm down the road — 20 acres of land that was the subject of much anger and anxiety on the reservation — and the tribe was counting on it.

One tribal official alleged that law enforcement from outside the tribe suspected arson, but no one was charged. Many people in the community suspected that someone had set fire to the gas station so they could make off with the cash. That was never proved. For most at Fort McDermitt, the damage was emblematic of something more troubling: a mismanaged venture that never realized its promise.

“We need to recover what we lost here,” said Jerry Tom, an elder of the tribe, whose relentless search for answers brought the community together this year. “Nothing good has come of the cannabis business.”

THE NORTHERN PAIUTE-Shoshone-Bannock people from Fort McDermitt call themselves Atsakudokwa Tuviwa ga yu, or People of the Red Mountain. Their territory, which straddles Nevada and Oregon, lies among wide expanses of sagebrush, with the nearest town, Winnemucca, Nevada, 74 miles away.

Driving up Route 95 from Reno, a person can go for hours without seeing another car. The road passes several landmarks important to the tribe, including a peak that served as a lookout when they were fighting army cavalry in the 1860s. Bitterness still burns about the exploitation of lands once governed by Indigenous people.

Tucked away in the high desert, the reservation offers little in the way of work. The lucky few have ranches, or work at the Say When Casino down the road, the tribal government or the school. Many trek three hours to Boise, Idaho, or farther to work in the mines.

Over the past decade, public attitudes and state laws around cannabis have relaxed, resulting in a booming legal weed market worth an estimated $35 billion nationally. In theory, the United States’ 574 federally recognized tribes have much to gain from it. In total, they retain about 56 million acres of land in federal trust on which to grow it, in addition to reservation lands. Being sovereign nations, they can largely use the land however they want, unimpeded by federal prohibitions on growing and selling marijuana. For Fort McDermitt in particular, profits from weed could translate into badly needed jobs and money for schooling and infrastructure.

But cannabis is a risky business. Bad weather can ruin crops. It can take years to turn a profit. Due to the federal ban on weed, national agencies do not regulate Indigenous marijuana enterprises as they would casinos, leaving supervision to the Native nations, which often face limited resources and restrictions on jurisdiction. (Fort McDermitt, for instance, does not have its own police force, so it must rely on the county sheriff and Bureau of Indian Affairs officers stationed an hour or more away.). Tribes generally can’t get bank loans from big banks for the ventures and aren’t familiar with cannabis cultivation, so they have to bring in outside experts and investors.

All of this and the cash-based nature of the business can make Indian Country vulnerable to deals that go wrong.

That’s exactly what happened when three white men from Oregon — Kevin Clock, Eli Parris and Darian Stanford — and their Native American collaborators sought to make money from Indigenous land. By the time they cleared out, seven years later, more than a gas station had gone up in smoke.

By the time the three white men had cleared out, more than a gas station had gone up in smoke.

IT WAS 2015, and the private investor Kevin Clock was looking for a win.

He and his friend Joe DeLaRosa had recently visited Vancouver, Washington, to check out a popular weed dispensary, and he’d had his eye on cannabis ever since. “We realized it was a moneymaker,” said Clock, whose background was in “development and land use and things,” speaking in an initial interview this spring. (He has since declined to answer further questions about the operation.)

That got him thinking about Nevada, where an initiative to legalize recreational weed was to be voted on the following year, and about Native nations, where he thought cannabis retail stores and farms could succeed. Clock, a boisterous character with a knack for working a crowd, believed he could connect with Indigenous communities because he had attended high school with Siletz people in Oregon and married a Native Hawaiian. “It’s a similar culture,” he said.

To help oversee future operations, Clock roped in Eli Parris, a quiet outdoorsman from Oregon with a background in real estate and finance who grew weed privately. To facilitate Indigenous outreach, Clock counted on DeLaRosa, then-tribal chair of the Burns Paiute of Oregon. DeLaRosa, who had previously worked as the financial manager in a car dealership, couldn’t convince his own community to open a weed operation, but the team thought he could persuade sister tribes to create a “Paiute pipeline,” whereby some nations would grow cannabis and others would sell it.

In January 2016, the group contacted the leaders of the Fort McDermitt Tribal Council, which governs the reservation, to propose developing a marijuana farm on tribal lands.

Clock and his associates promised to bring in the necessary funding to get the operation off the ground. They said the farm would be 100% owned by the tribe and that the venture could create much-needed jobs and generate money to improve roads, housing, education and health for years to come. The project could also serve as an anchor for other businesses in this remote area.

Hearings were called on the reservation to present the proposal to the community. Cars filled the parking lot and people crowded into the building. Several tribal members who were present recalled promises that the farm would enrich the tribe. Some interpreted that to mean that they would each get a per capita share of the profits, one way that revenues from tribal casinos are distributed.

But some community members had concerns about whether it was legal to lease land to the cannabis operation. Many of the older residents feared that introducing a marijuana business would worsen the substance abuse problems already plaguing the community. Others found Clock pushy.

“They came in and painted a pretty picture and promised the tribe this and that,” said Arlo Crutcher, a local rancher who attended the public meetings. (Crutcher became tribal council chair a few years later.) “I said, ‘This doesn’t sound too good.’”

He felt the men dodged questions about operational matters and didn’t allow time for tribal officials to seriously consider the offer.

Crutcher thought others in the community were too trusting of the men’s pitch. He noted that his tribe lacked the business savvy of richer nations with long-standing businesses. Fort McDermitt had never had an enterprise of this scale. “The investors knew they were dealing with gullible persons, and they took advantage of that.”

Still, representatives from Fort McDermitt reached an agreement with Clock’s team in November 2016, heavily pushed by Tildon Smart, who soon became the tribal council chair. They established a 10-year partnership that would first pay Clock’s company back any investments and then give it 50% of revenue, an unusually large cut for businessmen not from the tribe. Like other tribal nations in Nevada, Fort McDermitt was to collect a cannabis sales tax to fund essential services in the community. The outsiders would take care of all the financing and operations.

Soon after, Clockbrought in Darian Stanford, a litigator who had worked as a deputy district attorney prosecuting gang violence and major felonies in Oregon, to help with legal matters. Attorneys from a law firm where Stanford eventually worked were retained at $400 an hour, and a five-member cannabis commission was set up by the tribal council and tasked with oversight of the operation to ensure things remained above board. The commission was supposed to be accountable to the nation’s ultimate authority: the tribal council. In an unusual move, Parris, an outsider, as well as two members from the tribal council, were on the cannabis commission, placing them in a position of supervising their own efforts.

According to Mary Jane Oatman of the Nez Perce Tribe, who helms the Indigenous Cannabis Industry Association, that should have raised a red flag immediately. “There was no system of checks and balances,” said Oatman, whose advocacy group guides tribes navigating the legal weed realm. “They have members of the tribal council taking off their hats and then putting on the hat of the cannabis commission. They should have had an accountability system.” (Smart and Stanford defended the practice, saying it allowed for the easy flow of information between the council and commission.) Stanford also became the tribe’s judge a couple of years later, putting him at the center of legal disputes in the community, though he recused himself from matters related to the business.

Around 2018, the newly created joint venture — Quinn River Farms, named for the ribbon of water that flows through Fort McDermitt — was hard at work, purchasing soil and farm equipment, leveling land, installing greenhouses and readying a building for storing and processing the harvest. Although Clock and his associates never became fixtures in the community, Parris frequently checked on the site. They brought in a foreman and hired dozens of tribal members who learned how to cultivate plants, cut buds and make pre-rolls. They were often paid in cash, a common industry practice but one that makes it hard to keep track of costs.

This was the vision: an emerald sea of towering marijuana plants that would change lives, with goods sold to another Paiute tribe and to businesses in Las Vegas, where new weed lounges and dispensaries were expected to open. Over the course of its operation, investors would pour in millions, in the hope that it would be so successful that it could set a standard across Nevada and for other tribes.

H/T: www.hcn.org