In June, Roland Conner sat down to compose a letter to the creditors who had financed the construction of his licensed cannabis dispensary in downtown Manhattan. A year and a half after opening, he was under immense strain as monthly loan payments, tax bills and obligations to his vendors mounted.

“Despite our diligent efforts, we are encountering severe financial difficulties that threaten the viability of our business. I am reaching out to seek your support and understanding as we navigate these turbulent times,” he wrote.

Conner’s past marijuana convictions had qualified him for a class of retail license awarded by New York State as a means of reparations to people who had been harmed by discriminatory policing of old drug laws. His store, Smacked Village on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village, was the second to open in the state and the first supported by the New York Social Equity Cannabis Investment Fund, a $200 million initiative to finance 150 dispensaries with a mix of public and private funding.

Conner’s wife, Patricia, left her accounting job to run the store’s finances and his 26-year old son, Darius, moved from Florida to work at the shop as well. Together, their family seemed a perfect example of who the state wanted to help most through its 2021 cannabis legalization by helping to build generational wealth.

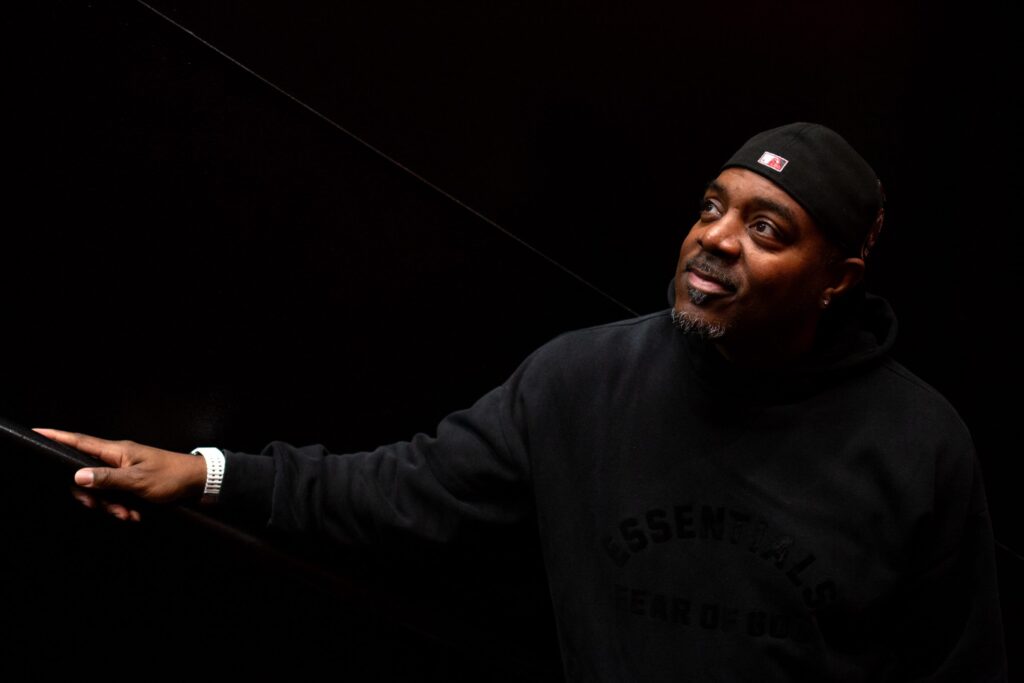

An affable man who owned a real estate company, Conner was chosen to be a face of the state’s bold initiative; he was one of the top scoring social equity applicants based both on his business experience and prior convictions. But since then, his store has struggled to live up its vision, ultimately hampered by a deal structure fashioned by the social equity fund that state officials vetted and agreed to.

Conner signed an agreement to reimburse the fund for about $1.9 million at a 13% interest rate over 10 years for the construction of his store. As part of that agreement, he is required to reimburse the fund for all operational expenses. From the start, costs ballooned as state and fund officials pressed Conner to open a trimmed down, temporary version of his store at a time when next to no dispensaries were opening despite an ambitious timeline set by Gov. Kathy Hochul.

The ribbon-cutting was a public relations success, with Conner and his family appearing in television segments and news reports, but in the rush to open, vendors for staffing, security and legal services racked up hundreds of thousands of dollars in charges, invoices reviewed by THE CITY show. On top of that, his store faced competition from a robust market of unlicensed stores that state officials initially failed to shut down.

Today, Smacked is in a precarious position, Conner’s business is challenged by tax bills, an increasing monthly loan bill from the fund and a lawsuit over an outstanding invoice for legal fees.

Meanwhile, the fund’s three managers and its private lender are prospering. Former City Comptroller William Thompson, sneaker entrepreneur Lavetta Willis and retired basketball star Chris Webber have raked in $1.7 million in management fees over a one-year period, THE CITY found, and stand to make millions more over the next 15 years whether they help open a single new store or not.

The company lending the private capital is in a no-lose position as well, after it stepped up with its own offer when the three managers failed to find investors willing to supply $150 million that Hochul had declared would comprise the bulk of the fund’s assets. Instead, the firm, Chicago Atlantic, signed a deal to loan the fund up to $50 million with a guaranteed 15% return. According to the terms, even if licensees like Conner default on their loans, the state will make the company whole.

Other than the licensees, should they default, the potential losers are the state’s taxpayers, who have invested $50 million in a fund that is currently draining money.

In a statement to THE CITY, the New York Social Equity Cannabis Investment Fund said that licensees were given a choice of whether to operate a pop-up store or wait until there was a full-scale launch and that “several ran successful pop-ups, which gave them the opportunity to gain experience and generate revenue more quickly.”

The fund’s statement continued: “While the vast majority of operators participating in the Fund’s program are enjoying success, we continue to support those who may be struggling to compete against thousands of unlicensed cannabis sellers or who are new to running a retail business.”

The governor’s office, the state Dormitory Authority and the Office of Cannabis Management, all of which work with the fund or oversee cannabis licensing, declined to respond to questions.

Chris Vianello, who operates two dispensaries in Massachusetts and first opened the fund-backed Dazed in Union Square as a pop-up last April, told THE CITY that the temporary operation had been helpful to launching the store.

“We definitely didn’t have a lot of time to prepare,” he said, while going on to call it a good opportunity “to do a test run of the market and see what works.”

Despite the challenges that he and other operators described in interviews, Conner maintains a strain of his optimism. With his business suffering runaway costs, the only pathway he saw was to ask for aid from the same people who had helped create his situation in the first place. In his letter to the fund, he requested a three-month grace period on his loan to give him time to catch up on his debts.

“Smacked Village was designed to be a template for the program, and we believe we can also serve as a template to address and rectify issues within the program,” he wrote.

Scramble at the Pop-up

Near the end of 2022, with the launch of the legal cannabis market far slower than anticipated, Hochul announced that 20 stores would open by the end of the year — even though at that point the fund had only signed nine leases and no retailers were close to operational.

That December, officials crafted a plan to open pop-ups within weeks instead of completed stores — bare-bones operations that could open quickly and be retrofitted later. Some officials inside Hochul’s administration and some licensees worried that any time saved or customers gained by opening quickly would be lost when the stores had to close to finish the construction.

“We strongly doubt the capabilities of even our best operators to pull something like this off in 3 weeks,” Ben Sheridan, a former policy director at the Office of Cannabis Management, wrote to his colleagues in a December 2022 email obtained by THE CITY.

The plan still moved forward. The head of the Dormitory Authority, the state agency that partnered with the fund to secure store leases and oversee construction, organized two days of training for retail licensees in early January at Smacked’s future location on Bleecker Street, emails show.

The state wanted Smacked to open in early January but was persuaded to push back to the end of the month. Even then, the timetable seemed implausible. Emails show that a week before opening, staff still had to be hired and trained; inventory had to be ordered and the bank accounts had to be set up to process transactions. The building’s heat needed to be fixed. And the fund had yet to turn over the keys to the store to Connor for what was supposed to be a run of only one month.

Both fund and state officials started looking for ways to speed things. They brought in a staffing company, Marcum Search, which hired 31 employees to work at Smacked right away. A representative from Dutchie, a company that offers a point-of-sale system for cannabis dispensaries, set up training for workers a few days before opening. Lawyers from the firm Prince Lobel Tye assisted with advising Conner. And within days, tens of thousands of dollars in products began pouring in, invoices show.

“It was just a mad dash,” Conner told THE CITY. “They wanted the store open because they were under pressure from the state to get these stores up and running.”

Conner signed an agreement to operate on a short term basis, but he hadn’t signed a loan agreement with the fund stipulating the costs that he would owe and at what interest rate. Early on, state officials estimated the final loans might offer $800,000 to $1.2 million at a 10% interest rate. At the time, Chicago Atlantic was still negotiating the terms of its own loan deal with the fund, which would in turn impact the terms of loans to storeowners, according to people knowledgeable about the terms.

“Tentative schedule for Monday! Details to follow! :-),” Willis, one of the fund managers, wrote in an email three days before the grand opening scheduled for that day.

The night before opening, Conner still didn’t have the keys to the cash registers, he recalled. He took a walk around the block to cool his frustrations.

“Okay, we just have to keep going forward,” he recalled telling himself. It became his mantra.

The next day, the opening went ahead as planned. State officials along with the cannabis investment fund managers lavished praise on Conner and his family at a packed press conference. “As part of the social equity program,” Reuben McDaniel, the CEO of the Dormitory Authority at the time, said, “Roland has a chance to make good money over the next four weeks.”

H/T: www.thecity.nyc