Between now and November’s election, there will be considerable discussion regarding rescheduling. Of importance in this discussion is the fact that marijuana remains at this moment illegal in all 50 states under federal law, so, for example, a dispensary selling marijuana products is acting criminally whether or not such sales are permitted under state law.

A physician accepting payment for recommending marijuana and filling out a relevant state form could be charged federally with conspiracy related to the sale of an illegal product. Also important in the discussion is the fact that marijuana is a plant, not a drug. The plant simply happens to contain psychoactive substances, along with thousands of other molecules, all of which may or may not have short- or long-term effects that have not been studied specifically.

Sufficient scientific evidence that the plant itself has beneficial medical utility is limited in scope and of poor strength, but several components of the plant do have such utility and have been separately Scheduled and marked as indicated for a number of very limited medical conditions.

The Controlled Substances Act places regulated substances into one of five Schedules based upon medical use, potential for abuse, and safety or dependence liability.

Under the law, eight issues must be considered to determine which Schedule is utilized for any one product. Five of the eight deal explicitly with abuse and dependence issues or risk to the public health. Two deal with scientific knowledge and medical utility and applicability. The remaining issue simply asks whether the substance is a precursor to another controlled substance.

We have pressure from multiple directions, including:

Industry – if we simply follow the money, we find a marijuana industry waiting to become the next recipient of the financial gains that typically follow utilization of a newly available addictive activity.

Science – we have knowledge that marijuana, as a whole plant, has not been sufficiently demonstrated as having true medical utility, and we have knowledge that the plant contains entities with significant addictive potential and negative impact upon public health.

Public policy – there are a variety of approaches that vary depending upon the precise issue being considered. Perhaps a doctor recommending marijuana use should not be at risk of indictment under federal law for doing so, or a facility selling a product that under state law is allowable should also not be at risk of federal charges.

Issues of decriminalization and legalization quickly become conflated with issues of rescheduling. And here it is crucial to understand that moving a drug from Schedule I to Schedule III does nothing to decriminalize or legalize it. Physicians specifically may find even more risks present should the plant be rescheduled.

Let’s play this out. Marijuana moves to Schedule III. Now physicians could no longer recommend patients obtain marijuana any more than they could recommend patients obtain codeine. They would need to write prescriptions for FDA-approved marijuana products, which would surely follow the rescheduling and which would be sold through pharmacies rather than dispensaries.

Such prescriptions would need to be written in the usual course of the physician’s profession to a legitimate patient. The DOJ generally interprets this as meaning that the physician follows standard guidelines in the field, but of course guidelines from professional medical societies say there is no appropriate use of whole-leaf marijuana.

The American Psychiatric Association specifically states that marijuana use generally leads to negative impact on psychiatric diseases. And the DOJ is not known for sitting back when physicians prescribe a controlled substance that leads to predictable morbidity in the absence of any well-established benefit. Meanwhile, manufacturing, selling, and using “recreational” marijuana would remain illegal, just as is the case for any Schedule III drug.

I should point out that at the moment, a Congressional appropriations rider is in place that has been interpreted as prohibiting federal prosecution of state-legal activities involving “medical marijuana.” The Controlled Substances Act itself was written in part, specifically, to protect physicians writing prescriptions for controlled substances, but for the past decade that same Act has been utilized to indict physicians writing prescriptions for controlled substances (for example, see here and here). Interpretations can change.

Rescheduling may potentially benefit the pharmaceutical industry but would not benefit the recreational cannabis industry. It would largely ignore the science. And it would likely impact public policy issues in ways that are quite different from those desired by various stakeholders.

If you’d like criminal justice reform or improved social justice, rescheduling will not achieve that. If you’d like marijuana to be available recreationally, rescheduling won’t achieve that either. If you prefer legislative acts to be based upon scientific evidence where appropriate, then you certainly don’t want marijuana rescheduled. At this point, the rescheduling maneuver appears to be borne from political desires within an administration hoping that the American public will perceive this as being a desirable lessening of restraints on a long-prohibited substance.

Indeed, it sends a message to the public that marijuana actually has medical utility – again, a message that has come only from our political community in the States, and now perhaps from the federal government, but never from anywhere but the fringes of the medical professional community. Ultimately, perception is the only truly important issue on the table, but our job as scientists and clinicians is to do whatever we can to protect the public health, to protect our patients, and to stand up for the scientific evidence, however unpopular that position may be.

A few years ago, ASAM released a Public Policy Statement on Cannabis noting that cannabis should be rescheduled. At the time, many of us had hopes that this rescheduling would involve a new Schedule such as Ia, which would permit greater access to clinical research while still indicating that the product had no, or at best, uncertain medical utility. I still agree with ASAM’s statement. However, without a new Scheduling option, we are left with the choice of existing Schedules outside Schedule I, all of which directly state that the product does have medical utility. That is the part which remains unacceptable.

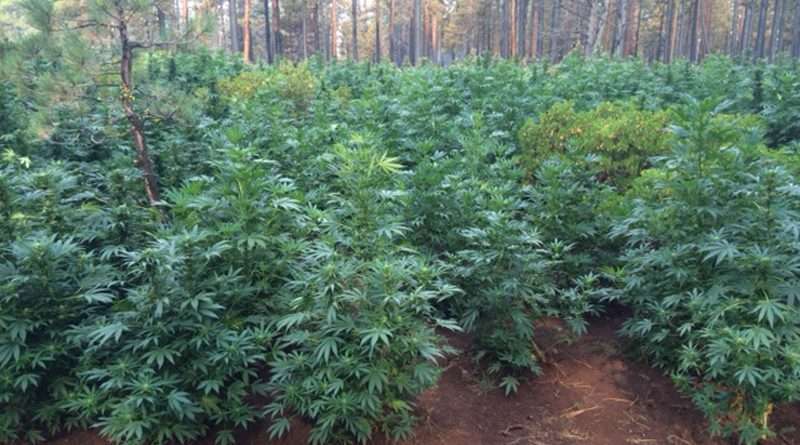

H/T: www.lassennews.com

You can view the whole article at this link Does rescheduling marijuana make sense?